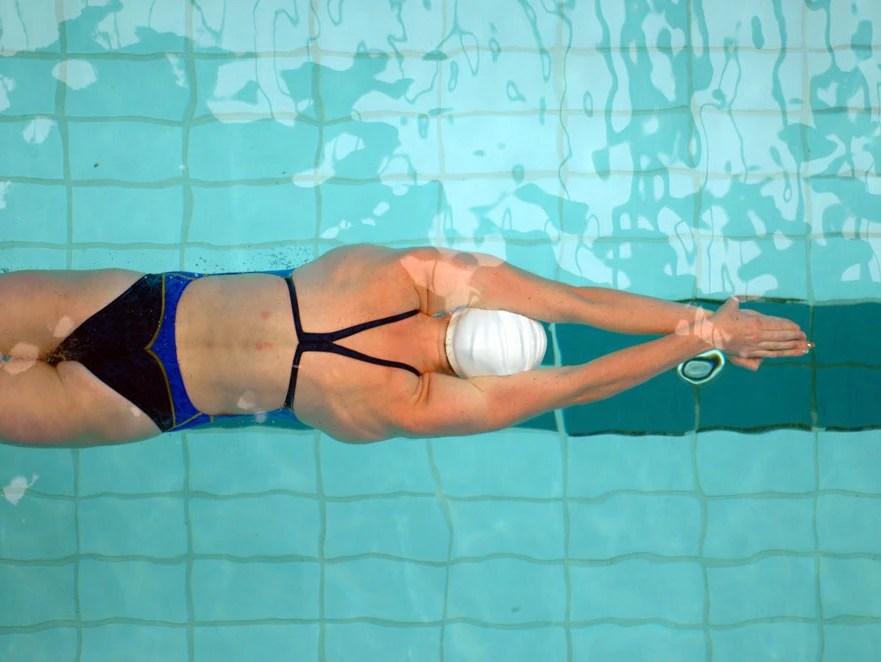

The Two Sides of Swimming: Hyper-mobility

The latest volume of ‘Orthopaedic Physical Therapy Practice’ featured an article titled, ‘Management of Hypermobility in Aesthetic Performing Artists: A review.’ The article breaks down joint hypermobility in performing artists and offers gems on how to manage hypermobile clients from a PT’s point of view. Needless to say, it got me thinking.

In my nearly 20 years of coaching swimming (😳), it has become very apparent that for the most part, swimmers come in two varieties. The generally hypermobile and the very stiff (to be discussed in a future blog). Coming at you as a swimmer (swammer?), swim coach and a physical therapist, I can tell you that hypermobility is also very prevalent in swimmers. Maybe not always in the generalized (multiple and usually bilateral joints with ranges of motion that exceed ‘normal’ and associated with Joint Hypermobility Syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome) sense, but at the very least in the low back and shoulder sense.

Hypermobility (often referred to as ‘double jointed-ness’) can absolutely be an advantage for swimmers – knees that hyperextend can improve kick propulsion with both flutter and dolphin kicks, hypermobile shoulders can allow for an increased length of pull in freestyle and backstroke. But it can also increase a swimmer’s risk of injury.

Mobility is defined as ‘the ability to move freely’ and encompasses flexibility, strength, neuromuscular control and yes, the actual range of motion allowed by the anatomy of a joint. Swimmers, much like pitchers in baseball or hitters in volleyball often have more range of motion into external rotation as compared to internal rotation, with an imbalance of strength noted with internal rotation being much stronger than external rotation.

Lost you? In swimmers, pitchers and hitters, force is generated as the arm comes down from overhead, across the body. Take this motion and repeat thousands of times over the course of a single practice, and adaptive changes will occur to the ligaments and tendons at the shoulder, and if not accounted for, can lead to shoulder pain in the form of rotator cuff tendonitis, biceps tendonitis or bursitis as well as other issues related to movement coordination (or the lack there of). Sound familiar? Probably. Studies have reported the prevalence of shoulder pain in swimmers as high as 91%.

So what’s next?

Pain, especially if it’s limiting your participation, should be evaluated by your PT. They’ll check for hypermobility as well as any imbalances in strength and flexibility that might be contributing to your pain and get you set up with a program to get you back on track. Strengthening and proprioceptive training to improve joint stability can decrease rotational hypermobility and prevent recurrence of pain and addressing muscular activation patterns can prevent common compensatory patterns.

The biggest take away here should be that if you’re hypermobile, you don’t need to stretch. Not only has research shown that passive stretching of a muscle can lead to decreased force generation (thus a decline in performance), but there’s no need to lengthen out tissues that already allow for more than normal range of motion. See your PT. Strengthen. Stabilize. And get back to swimming!

Comments 1

Years ago while on a health kick, i had lost about 30 lbs and had joined a local gym with a pool. I can’t swim in a straight line and am not a huge fan of having my face in the water, so I am doing a breast stroke and the turn over on my back, kick off the wall and return to the other end of the pool with a t-stroke. There was a loud pop in my shoulder and when i got out of the water I couldn’t raise my arm without severe pain. Coincidentally I had started takjng statins and blamed those, when I read that using those could effect your tendons. I went off of those meds and it took me 3 months to regain use of that arm. I am learning all these years later about hypermobility after a diagnosis of ADHD.. I am wondering if hypermobility played a role in the causation of my injury?